Technopolis Group provided the support study for the impact assessment of the new legislative proposal on new genomic techniques for the European Commission, DG SANTE.

Background

Scientific advancements in plant breeding technologies, particularly new genomic techniques (NGTs) like CRISPR-Cas, have revolutionized the field by speeding up the research and development process and allowing to create plants with specific desirable traits such as higher yield, pest, or drought resistance, or improved nutritional value.

A 2018, the European Court of Justice (CJEU) ruled that organisms obtained through NGTs are genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and fall under the scope of EU legislation on GMOs. This decision has sparked a debate on the classification and regulation of NGTs. While NGTs involve genetic modifications, they do not introduce foreign genes (as classical GMOs do), and many argue that they should be treated similarly to conventional breeding methods.

A study by the JRC in 2021 concluded that the current legal framework is inadequate. As a result, the EC initiated a formal impact assessment process. In April 2022, Technopolis Group, together with Arcadia International and Wageningen University & Research were tasked to provide the support study for this impact assessment.

What are NGTs?

In plant breeding, combining multiple traits by crossing and selection is a slow and tedious process that involves eliminating all offspring with one or more undesired traits. Breeding thus easily takes 20 years, for complex traits even longer. Plant breeders seek for new tools to remove barriers, accelerate steps, and improve precision and efficiency in breeding programmes. Merthods such as hybrid breeding, radiation-induced mutations, tissue culture, genetic modifications (GM), and DNA sequencing makes breeding based on crossings more efficient but not necessarily faster. For that, the new genomic techniques are relevant. These include cisgenesis and intragenesis, which introduce genes such as disease resistances from other varieties of the same species or crossable related species. Gene editing such as CRISPR/Cas can be used to induce targeted mutations in or near specific genes (SDN-1) or use a short template to copy desired changes that exist in other varieties or in wild relatives (SDN-2) directly into breeding lines. SDN-1 and SDN-2 are also termed ‘Targeted Mutagenesis’. In case of an insertion of a foreign gene (SDN-3), classical GM plants are produced.

What are the objectives for a new legislation and how did we address them?

The EC had set a few parameters what a new legislative proposal should entail:

It should help maintaining a high level of protection of human and animal health and of the environment and thus keep the precautionary principle.

It should also enable the development and commercialisation of plants and plant products that would contribute to the innovation and sustainability objectives of the ECs policy strategies such as the European Green Deal.

And finally, a new legislation should have an economic impact: enhance the competitiveness of the EU agri-food sector and provide a level-playing field for its operators.

With these three general objectives in mind, the EC developed a few so-called options. The current situation with the GMO legislation is treated as ‘Baseline option’. Other options included combinations of key components: adapted risk assessment, labelling and traceability requirements, sustainability incentives, and sustainability requirements. These options were then transformed and described by the study team in form of scenarios.

Yet, the study team was confronted with two limitations:

- Lack of data – there are no NGT plants in Europe and very limited experience in third countries, so that there is virtually no available data on economic, social, or environmental impacts of NGTs.

- Polarized debate. The use of modern biotechnology in agriculture and in particular GM food was and is still subject to emotional debates.

How to deal with these limitations? To start with the polarisation of the field, a key component was a balanced consultation of stakeholders. We identified key business associations, private-sector and research organisations, NGOs, and competent authorities, conducted about 60 interviews and invited 400 stakeholders to a targeted survey. A public consultation that was run by the EC equally provided feedback mainly from citizens.

The polarization of the field was felt early on – while it was easier to explain and debate in an interview with the various stakeholders individually, several– in particular from the organics and GMO-free sector – refused to participate in the survey. They felt that the EC would want to ‘deregulate’ in all the proposed scenarios.

The second limitation, the lack of data, we addressed with using a proxy: the costs of GMOs. Although there is limited experience in Europe with cultivation, through extensive discussions with public authorities and plant breeding companies and data from a wide set of public reports, we established cost ranges for different categories (e.g., authorization costs, coexistence costs), and for different actors (public national authorities, EU-level, the organic sector etc.).

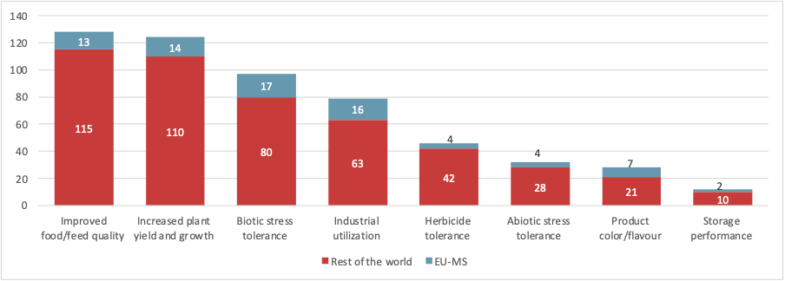

Obviously, there is a large body of literature – given the longer history of GMOs and their growth in the Americas and Asia, there is data and experiences. Through small, in-depth case studies we also draw lessons from the experiences abroad. While there is currently no NGT-based plant or plant product commercially available, there are hundreds of research projects around the world using predominantly CRIPR/Cas. Herbicide tolerance, which is one of the reasons for the negative image of GMOs, is in fact not widely researched trait. Improved quality, yield, and biotic stress such as draught or temperature are the key research topics (see below).

NGT research on traits related to…

Imports and the challenge of detection

Europe is importing and exporting GM, conventional as well as organic food- and feedstuff such as soybeans, maize, wheat etc. Several key agricultural producing countries such as the USA, Canada, Argentina, or Brazil have a more liberal regime for induced mutations that could have occurred through natural processes. They do not distinguish between NGT-based products and conventionally bred cultivars.

Common or specific genetic characteristics that are being used as a target to detect and to quantify GM plants are often not available in genome edited plants, challenging the implementation and enforcement of the current EU regulatory system. If the genetic alteration introduced by NGTs is not unique for the relevant product, a specific detection method cannot be provided. Although existing detection methods may be able to detect small alterations in the genome, this does not necessarily confirm the presence of a regulated product, as the same alteration could have been obtained by conventional breeding. It thus requires information about the application of NGTs and the introduced alterations to identify them in NGT products. Traceability would therefore be difficult to enforce in the international setting. The existing different and differing regulatory regimes and standards may in the end prevent a level-playing field for various actors of the value-chain.

Environmental effects

A much-debated question concerned environmental effects. Do NGTs lead to an increased or decreased use of pesticides, herbicides, fertilizer, water? Do they impact soil quality? The answer is somewhat unsatisfactory: it depends. A plant may be designed to need less water, but if the farmer still waters more than is needed, the positive effect of the trait does not manifest. Interviews and a focus group on sustainability strongly pointed out that the circumstances at the (micro) farm level and – highly important –the farming system matter tremendously.

Organic and GMO-free sectors

The organic and GMO-free sectors are strictly against any legislative change. With dedicated segregation streams separating organic food and feedstuff from conventional imports, buffer zones and a labelling system, the organic and GMO-free farmers have already higher costs than conventional farmers, but they equally have a higher premium. With a rise of NGTs worldwide, organic breeders will have more and more difficulties in finding organic seeds, a problem that is already acute and that adds to their costs. Costs may further increase due to more buffer zones or alternative (delayed) planting dates.

Consumers

Currently, consumer choice is rather limited since there are no GM or NGT products on the shelfs. Would consumers buy NGT products? There are obviously numerous customers who would not want to buy them. There are however several surveys indicating that younger generations in Europe have a higher willingness to buy NGT products if they offer sustainability benefits. Obviously, without having products on the market, the discussion on consumers is highly speculative and the industry recognizes that this is the by and large the unknown in the equation.

Which option to choose?

The analysed options vary in terms of achieving the specific objectives (effectiveness) – and in terms of costs (efficiency).

The analysis confirmed that under the current legal framework – the Baseline option –the mentioned objectives cannot be achieved. In fact, regulatory costs and administrative burden are maintained and remain prohibitively high for SMEs and newcomers. Given the expected regulatory divergence between the EU and third countries, enforcement and traceability costs are expected to increase for all, including the organic sector. Due to the limited detectability and differentiability of NGTs, there is a risk of presence of NGTs in imported (and subsequently processed) food products while consumer choice would remain limited to conventional and organic products. There are substantially negative impacts on plant breeders, competitiveness, trade, R&D, and more moderately, on farmers and the wider value chain. The relative competitiveness of SMEs in plant breeding would also not improve. Social and environmental opportunities for improving health, environment, and global food security may not be realised timely.

The option of an adapted risk assessment and detection requirements was not well received by industry mainly due to expected (still) high costs. It would lead to a certain level of NGTs on the market which would potentially impact the costs of the organic market to avoid admixture (buffer strips). Yet, since traceability and labelling would remain, this would suit the organics sector.

The (sub)options of authorization with sustainability incentives obtained mixed opinions. In particular, a sustainability label was met with scepticism by all stakeholders. The main weakness of this option is the uncertainty of what would be considered a sustainable trait. Stakeholders fear that these considerations may not align with actual sustainability in farming systems.

Notification for certain products obtainable by natural/conventional plant breeding – is the preferred option by several, but not all stakeholders. The option has the potential to have a considerable number of NGT plants with positive environmental effects developed after 2030. Thekey uncertainty in this scenario is the evolution of consumer preferences and awareness of the NGT topic up to 2030 and beyond. This could greatly impact the demand for those products. The expected growth would encourage investments in R&D, scientific and technological developments, and strengthen the knowledge capacities in the EU. Whether or not SMEs benefit substantially is uncertain; this depends to some extent on their capacities to obtain affordable licences to use these, often IP-protected, technologies. This option has main impacts in costs. Plant breeders may benefit from the most substantial cost reductions (between 70% to 90% of total authorisation costs depending on the system put in place). For SMEs such substantial cost reduction is expected to lead to more SMEs and newcomers entering the market of NGTs. Depending on the level of adoption of NGTs, various impacts can be envisioned: higher costs for the organics sector, investment needs of the regulating authorities but available plants that help reducing environmental pressures.

In essence, every legislative change comes with several potential positive and negative impacts. They are positive for economic operators, research and innovation actors, consumers, and the environment. Yet, there are also risks for the established organic and GMO-free sectors.

Given the high environmental, social, and economic potential, should the EU maintain the legal status quo? The EU requires food and feed imports. It is expected that the segregation costs for securing conventional and organic food and feedstuff from GMO and NGT plants from abroad will increase and be passed on to the European consumers. NGTs can become a key component for a sustainable agriculture and food security in the EU. For this to happen, it is also advisable to seek coherence with other parts of the wider legislative framework such as intellectual property rights, as well as farming systems.