According to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the new Paediatric Regulation has significantly improved the regulatory environment for paediatric medicines in Europe. But how much has it changed the paediatric research landscape? How has it impacted on the economic environment for industry? And to what extent has it enabled the development of new medicines for children?

The Paediatric Regulation

The development of paediatric medicine in Europe used to be hampered by weak economic incentives (many markets for children’s medicines are small) or impeded by ethical questions. Doctors routinely resorted to prescribing medicine that was not tested and approved for children. However, it is now widely recognised that children, who make up a fifth of Europe’s population, are not small adults but have age-specific physiology and therapeutic needs. The Paediatric Regulation, introduced in 2007, sought to stimulate greater research and development of medicines for children. A decade on, a report1 on the Regulation’s socio-economic impacts provided key inputs to the Commission’s comprehensive ‘State of Paediatric Medicines’ document.

The Paediatric Regulation combined new legal obligations with economic rewards for the pharmaceutical industry, aiming to stimulate research, innovation and medicinal product development. For marketing authorisation of any new (including adult) medicinal product, sponsors have to develop a so-called ‘paediatric investigation plan’ and conduct studies to gather data on whether the medicine is safe and effective for use in children. For those completing such plans, the Regulation foresaw economic benefits through patent extensions or prolonged market exclusivity for the product.

Effects of the Regulation

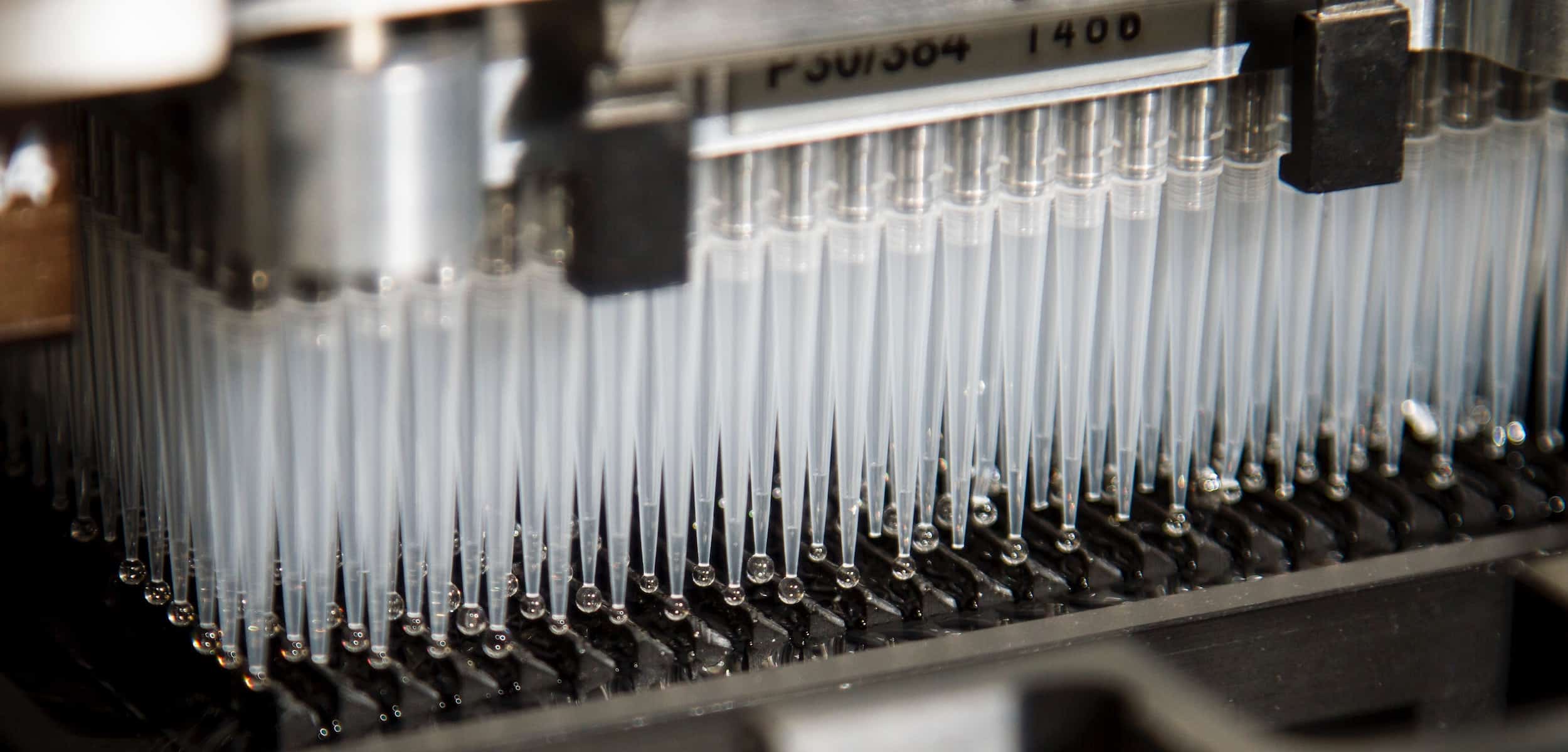

Gaining access to information on the costs incurred by pharmaceutical companies for paediatric clinical studies made it possible to develop a novel cost-benefit model. To our knowledge, firms have never before made their data on paediatric trial costs available to an independent research organisation to construct an economic assessment.

The report analysed data for 85 paediatric investigation plans from 24 organisations, and this made it possible to estimate that compliance with the Regulation costs pharmaceutical companies overall about €2bn per year. This is a small amount when compared with voluntary R&D investment by companies in adult medicines. Nevertheless, with about 1,000 new paediatric investigation plans agreed and over 100 already completed, the Regulation has resulted in a considerable increase in scientific knowledge, new networks, and high-quality information published about medicines used by children.

The economic value of the Regulation to industry is harder to estimate or set against the costs already incurred. This is because pharmaceutical companies will reap the benefit many years after completing paediatric clinical studies, if at all. In addition, the promise of future rewards cannot guarantee a positive return on investment in individual R&D programmes. This explains why companies are reluctant to develop paediatric medicines voluntarily – especially for less common diseases, where the biggest unmet paediatric needs lie.

As an example, the report analysed eight medicinal products in detail for a range of therapeutic areas where the reward of a patent extension has already been realised and estimated the direct and indirect benefits that would accumulate over a period of 10 years. The results showed a large variation in terms of net benefit to society: while some products provided €32-66m net benefit, others resulted in negative net benefit ranging from €4m-€166m. Extrapolating these results to all completed paediatric investigation plans so far suggests that overall the Regulation balances the compliance costs to industry and the benefits to society.

What next?

The Paediatric Regulation was an important first step to improve access to safe and effective medicines for children. However, many stakeholders fear that the value generated by the application of the Regulation may be lost if clinicians do not make use of the new medicines. Investments in paediatric R&D will only translate into better treatment of children and lead to tangible social and economic value if mechanisms are put in place to ensure that the newly acquired knowledge is put to good use by practitioners. While some therapeutic areas are ‘crowded’, others are not covered at all by current paediatric investigation plans. In addition, the Regulation provides little incentive for developing much-needed ‘paediatric-only’ medicine, where markets are small. Some of the most staggering examples relate to paediatric cancers, the number one cause of death of children by disease in Europe. A separate piece of legislation (the ‘Orphan Regulation’) has been effective in attracting innovative products for rare adult conditions, and so the European Commission is taking now a closer look at the combined effects of the Orphan and Paediatric Regulations.