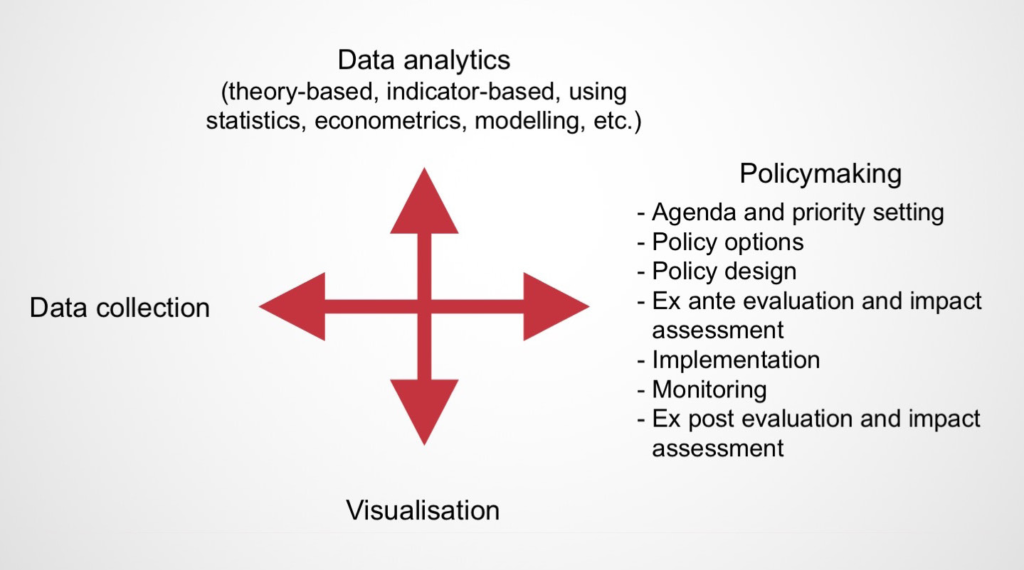

‘Big data’ is about high-velocity, high-variety and high-volume data sources — such as sensor data, social media data, transaction data and satellite data — and about methods to analyse data and visualise the results. Using big data has become the norm for companies such as retailers, online media providers and insurance companies. Policy makers, however, have only started to explore the opportunities of using big data. This holds for explorative policy analysis that seeks to understand societal developments and transitions, and indeed for data collection and analysis for the design, implementation and evaluation of concrete policy interventions.

Over the last two years, Technopolis Group has had the privilege to analyse the use of big data by national and international policymakers. In a study for the European Commission (EC), Technopolis Group, the Oxford Internet Institute and the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) interviewed thought-leaders, identified 58 state-of-the-art ‘data4policy’ initiatives, and organised an expert workshop. Our client was the EC’s DG CONNECT. Several DGs were involved in scoping the study and in developing 10 use cases for the European Commission, in areas such as education, health and trade policy.

One of these use cases, on bee health, was developed into an online demonstrator. The concept should be applicable to many other policy areas that could benefit from realtime, continuous sensor monitoring combined with a comprehensive set of environmental and policy data that can be linked at the local, regional, national and EU level. Showing such combined data in a unified visualisation and analysis interface allows explorations and inferences that may not be apparent by looking at individual data sets.

The results of the study are available at www.data4policy.eu

Trends and observations

- An overarching observation is that the use of big data by policymakers increases step-by-step, depending on the specific characteristics of policy areas, policymakers and the added value of new data sources. For instance, when official statistics based on large-scale surveys are lacking, or when the results are available too late, the incentives for using new data sources are substantial. An example is the use of mobile phone data (location data) to estimate population density, traffic flows and trade flows in developing countries.

- Smart cities and local policymakers are well ahead of national and international policymakers, for several reasons: public-private collaboration and citizen engagement are easier to organise at a local level, sensor networks can be installed quickly at the city level, and local policymakers can clearly communicate the advantages of big data approaches, for instance when providing citizens with access to data about air quality, parking spaces and safety.

- National and, to a lesser extent, international policymakers are starting to use big data in areas such as transport, labour markets, and economic and environmental policy. Examples are the use of vehicle detection sensors to monitor traffic, text mining of vacancy databases to assess skills shortages, web scraping online retail websites to monitor inflation, and using sensor data to monitor water quality

- New data sources, such as social media data and other types of web data and unstructured data, are used in many research and innovation projects (such as Horizon 2020) but the actual implementation by policymakers 2020) but the actual implementation by policymakers developing and testing new data sources, and addressing barriers related to the regulation of data ownership, protecting privacy, the skills of data scientists and users, organisational routines, risk-aversion and cost, when implementing and scaling up these new data sources.

- A similar evolution can be observed for the use of advanced analytical tools such as machine learning, profiling and predictive analytics such as ‘nowcasting’ (providing continuous forecasts of the near- and medium-term future). These tools are developed and used in research projects, while the emphasis in applied policy analysis is still on descriptive statistics.

- Along the same lines, big data is used mostly during the first half of the policy cycle (e.g. foresight, problem analysis and policy design), while only slowly we see applications emerging in interim and ex-post evaluation and impact assessment (an example of so-called altmetrics is web scraping to assess the visibility of research institutes).

- There is a certain hype element to big data but, if we unpack the concept and take an evolutionary perspective, we can see a risk of underestimating its impact. The possibilities for using big data for policy will increase as new data sources become more widely available (with some data being generated automatically, as a by-product of other processes), data linking becomes more feasible (benefiting from open data and using unique identifiers for regions, industries, technologies, etc.), analytical tools are improved (in functionalities and user-friendliness) and online visualisation tools become more intuitive.

- Important challenges for using big data in the policy process, as opposed to using big data in companies, are the requirements for transparency, accuracy and accountability: in short, no ‘black-boxing’. For instance, algorithms must be understood by policymakers and the main elements communicated to politicians and citizens. Moreover, when data sources such as social media data are biased towards certain age groups and income levels, additional data sources are needed to ensure that all voices are included in the policy process.

- Another challenge is to find a new balance, between explorative research approaches using the abundance of data on topics such as technology, innovation and economic trends (‘ask the data’) and carefully selecting the indicators and data that are most relevant for analysing such trends and assessing the impact of policy interventions (‘start with the intervention logic’). To rely too much on readily available data brings the risk of using irrelevant data. For instance, popular studies based on Twitter data and Google search entries turned out to be far less rigorous and relevant than was expected at the time of their publishing. In short: there are lies, statistics and big data.

- One of the opportunities of big data is dual learning: launching policy experiments and setting up a data collection and data analysis strategy to monitor and assess how policy interventions change the behaviour of actors. We should acknowledge the limitations of established data sources and collect both types of data. Moreover, stakeholder engagement remains crucial (or becomes even more crucial) for interpreting data, creating insights and improving policy interventions.